THE NEXT PANDEMIC: H5N1 and Why You Should Be Paying Attention By Evan Anderson Why Read: This week, we cover what everyone should know about the ongoing H5N1 outbreak, why it's deadly serious, and what might be done to avoid walking straight into another pandemic. ________ The flu is very unpredictable when it begins, and in how it takes off. [. . .] The key now is to do everything in preparation and to get all of our necessary elements lined up over the summer. - Harvey Fineberg, then- president of the Institute of Medicine, discussing the 2009 outbreak of swine flu Flu pandemics are nothing new. Medical historians think the first one struck in 1510, infecting Asia, Africa, Europe, and the New World. Between the years 1700 and 1900, there were at least sixteen pandemics, some of them killing up to one million people. Yet these were tame compared to the 1918 calamity. It was by far the worst thing that has ever happened to humankind; not even the Black Death of the Middle Ages comes close in the number of lives it took. A 1994 report by the World Health Organization pulled no punches. The 1918 pandemic, it said, "killed more people in less time than any other disease before or since." It was the "most deadly disease event in the history of humanity." - Albert Marrin, Very, Very, Very Dreadful: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 On March 11, 1918, a US infantryman fell ill with a sore throat, cough, and fever in Fort Riley, Kansas. Within a week, 522 more soldiers at the fort were also reported sick. Within the span of a few months, the entire globe had been hit with what would turn out to be the deadliest influenza pandemic yet known to man. An estimated 675,000 Americans died. Today's global estimates range from 50 million to 100 million fatalities. By now, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we have become more accustomed to hearing tales of the 1918 flu. That pandemic serves as a strong reminder of many facts: that we have been "lucky" so far with COVID, that infectious diseases are one of the greatest threats to human life, and that "It's just the flu" isn't the reassurance that some may believe. Influenza loves a good host and a crowded environment. Thus, our most common encounters with it tend to stem from regular interactions with the animals who host it best. The 1918 pathogen (H1N1) was, as it turns out, a type of swine flu. (Many of us will recall the 2009 swine flu, which briefly went pandemic.) Pigs are an excellent breeding ground for influenza viruses, especially when living in crowded conditions, and are biologically similar enough to humans that they make for great sources for a zoonotic jump - the moment when a pathogen moves from one species to another. Birds, like pigs, also often live in crowded conditions, and regularly experience influenza outbreaks. If you were to predict the next pandemic with closed eyes and an infectious-disease background, the most obvious one would be an airborne bird or swine flu, incubated somewhere in Asia. Lucky for us, avian flu has traditionally had a harder time jumping to humans than other flus (though sporadic infections do occur). In any given year, though we don't always know it, avian flu is usually spreading in one flock or another of wild birds. (The CDC has a useful timeline of various detected subtypes and human cases throughout the years here.) This is concerning, but generally outside of our control, and it doesn't necessarily pose a great danger to human beings in and of itself. What does pose a threat is the spread of avian flu to domestic birds, with which we have a great deal of contact in the packed henhouses of modern chicken farms. This has been an ongoing battle. Most of us have heard of occasional mass culling on chicken farms in attempts to stop outbreaks of bird flu. Far more alarming, though, would be a jump from birds to something more akin to people - say, a mammalian species - with sustained transmission between individuals. This would suggest that the virus had mutated sufficiently to allow infection of a new type of host, one much closer to humans in its makeup. Enter today's flu strain.

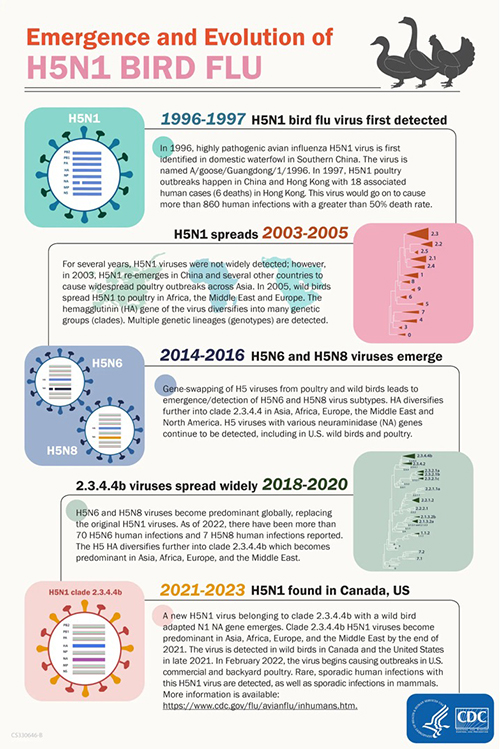

Scientists are warning people to "be alert" as bird flu continues to adapt and change. This is because the pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has just crossed a new frontier, a new study reported. It is spreading among marine mammals in an unprecedented outbreak that has killed thousands of elephant seals. This development raises concerns about the virus's adaptability and potential implications for human health. - Newsweek (6/6/24) In 2020, a massive bird-flu pandemic swept the globe. This was a new variant of H5N1. (The H and N in flu subtypes refer to the surface proteins hemagglutinin and neuraminidase.) Avian flu is also designated by its pathogenicity, or its ability to cause disease, as either low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) or highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). The 2020 variant of H5N1, first detected in wild European birds, proved more deadly than previous variants, leading to massive die-offs in wild bird populations around the world. Since influenza is notorious for its ability to infect large numbers of animals and mutate constantly, what came next should not be a surprise.

Infection of domesticated bird populations followed. Large culls have been ongoing since, as bird farms detected outbreaks through monitoring and rushed to stop the outbreak by killing the infected. This was already "not good," as it meant that poultry workers were regularly being exposed to a potential pandemic pathogen in unsanitary and enclosed work environments. But if the outbreaks on poultry farms were concerning, what came next, in 2021, was downright alarming. The virus jumped not only to many other species, but to species that included mammals. First seals, then foxes, minks, sea lions, and others all began falling ill. The H5N1 clade currently in question, 2.3.4.4b, was infecting and killing minks in Spain by October 2022. In November of that year, a human adult in China contracted H5N1 and died. In December 2022, H5N1 was found in bears across North America. Other 2022 outbreaks were discovered in seals in Maine; foxes, otters, lynxes, polecats, and badgers in Europe; and foxes in Japan. The first infections discovered in January 2023 involved a critically ill child in Ecuador and two people in Cambodia, one of whom died. The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) reported the Ecuadorian case on January 18, as follows: The girl's first symptoms, reported on Dec 25, were conjunctivitis and a runny nose. A few days later her condition worsened, she developed gastrointestinal symptoms, and she was hospitalized and empirically treated for meningitis. On Jan 3, she was transferred to a pediatric hospital in critical condition and was admitted to the intensive care unit, where she received treatment for septic shock. She was treated with antivirals and mechanical ventilation for pneumonia. A respiratory swab collected on Jan 5 was positive for H5 influenza. She remains hospitalized in isolation and is on noninvasive mechanical ventilation. The investigation into the source of her illness revealed that her family had recently acquired poultry, which died suddenly before the girl became ill. Several other deaths in backyard poultry were also reported in the same community in Bolivar province. As 2023 concluded, elephant seals and fur seals in Antarctica and a polar bear in the Arctic were all found to have contracted H5N1. Hundreds of seals, and the polar bear, ultimately died.

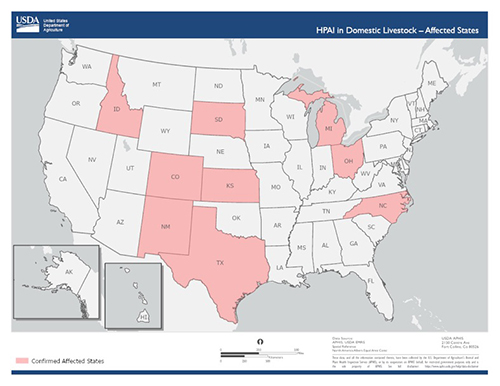

Currently, HPAI A(H5N1) viruses circulating in birds and U.S. dairy cattle are believed to pose a low risk to the general public in the United States; however, people who have job-related or recreational exposures to infected birds or mammals are at higher risk of infection and should take appropriate precautions outlined in CDC guidance. - CDC website (June 2024) And now we arrive at the elephant in the room. The year 2024 has seen the introduction (or at least detection) of clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 in cattle across the United States. In context, this is not a surprise. However it got there, we knew already that it was circulating among countless mammalian species. Finding it closer to home (or in your home, if you consume cow dairy) was probably just a matter of time. But if we were to gauge the level of "not good" we've now reached, we would have to say it's epically greater than what had been happening to date. Here is the distribution of infected cattle farms across the United States as of June 4:

We can now add Minnesota and Iowa to the Confirmed Affected States category, as it was announced just before we went to press that H5N1 has been found in cattle in both states. There are myriad problems with this. First, having rampant infections in American cattle obviously places workers on dairy farms and ranches at risk. This is a highly pathogenic virus, known to be a potential pandemic risk, circulating right in the middle of the American heartland. Clearly, we should be testing all at-risk workers, requiring personal protective equipment (PPE), testing animals, and seeking to cull or quarantine infected animals when we find them. None of those things are happening. In fact, when the first human infection occurred, in Texas in March 2024 (symptoms were mild, according to authorities, although the picture below seems to indicate otherwise), the response was curtailed by the other workers and the farm itself.

Conjunctivitis in the Texas H5N1 patient. Source: New England Journal of Medicine According to the Appendix of an investigation of the Texas case published in the New England Journal of Medicine: While acute conjunctivitis is a clinically mild illness, HPAI A(H5N1) viruses, including those belonging to clade 2.3.4.4b, pose pandemic potential and have caused severe respiratory 5 disease in infected humans worldwide; therefore, rapid implementation of preventive measures is recommended to reduce human exposures to any infected animals and environments contaminated by them, including to cows and unpasteurized cow milk. People should not consume unpasteurized milk and products made from unpasteurized milk produced by farms with cattle suspected or confirmed to be infected with HPAI A(H5N1) virus. [. . .] In addition to preventive measures that include hand hygiene and recommended personal protective equipment for workers, active surveillance for acute respiratory illness and conjunctivitis with influenza A and A(H5) virus testing of symptomatic persons at dairy farms with confirmed or suspected HPAI A(H5N1) virus infections of cows are recommended to identify additional human infections with HPAI A(H5N1) virus and to understand the risk to public health. Exposed persons should be monitored for any illness signs and symptoms, including conjunctivitis, and symptomatic persons should be immediately isolated and started on antiviral treatment with oseltamivir. Close contacts of confirmed H5N1 case-patients should be administered post-exposure antiviral prophylaxis (oseltamivir treatment dosing) and monitored closely for the potential of human-to-human transmission of HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Seroprevalence surveys among exposed persons may be helpful to assess evidence of 7 unrecognized human infections. Vigilance is needed because if HPAI A(H5N1) virus adapts and becomes established among cows or other mammals, the risk to public health may increase. Also according to that study: Taken together, our findings are suggestive of human infection occurring in the dairy farm setting and cow-to-human transmission of HPAI A(H5N1) virus from presumptively infected cows to an exposed dairy farm worker. However, we cannot exclude fomite transmission because no specimens from cows or environmental samples were available from the worker's farm for testing, and epidemiological investigations were not able to be conducted at the farm. The suggestions in the study are sound. This is a succinct description of how to stop a pandemic using the modern tools at our disposal. The fact that all interventions are currently optional is not only ridiculous - it is also inherently representative of the failure of public health authorities and the government to follow one of their most sacred duties: protecting the lives of their citizens. Pandemics simply cannot be prevented if everything that might be done to stop the spread of a novel pandemic pathogen is addressed on a "you do you" basis. And the current lack of testing and surveillance is appalling. Keith Poulsen, DVM, PhD, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, was recently quoted in a JAMA Network article as saying: "No animal or public health expert thinks that we are doing enough surveillance." He's right. And anyone in the field of infectious disease who pretends that this isn't a situation desperately in need of a more robust response by far than what we have seen to date is either willingly dishonest or simply incompetent. This thread of events is exactly what public health officials should be trained to watch for and respond quickly to. "Early detection, early response" is a now well-known adage in public health. There's an obvious reason for that: with a highly pathogenic virus (or any other dangerous pathogen) that has the ability to spread quickly, an outbreak cannot be brought "back under control" once it has spread too far. By the time a few cases are detected, there are often far more in the population, and the best hope the world has of avoiding a devastating pandemic is getting the first cases isolated and stopping the spread in the outbreak's earliest days. After that, all bets are off. Look at COVID. Now, two more cases have emerged in Michigan. The first looks a lot like the Texas case: "mild" symptoms, conjunctivitis, apparently recovering. The second is more alarming. Also according to JAMA Network: The latest case in Michigan involved eye discomfort with watery discharge but also upper respiratory symptoms, including cough without fever, according to the CDC. The person is recovering. This is particularly concerning because respiratory infection and coughing implies the potential of airborne spread. While there is no indication yet of any human-to-human transmission, this would be the next step in a viral evolution toward that possibility. A robust, all-hands-on-deck response is clearly needed. Instead, it's awfully quiet out there.

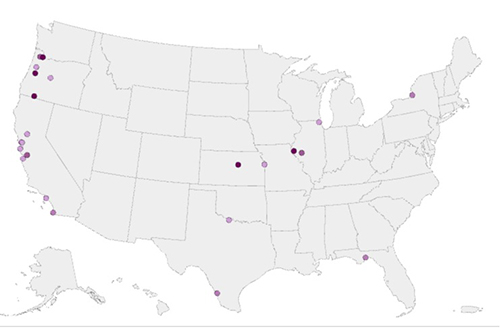

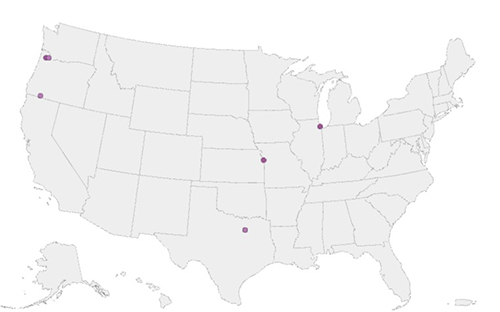

"What We Have Here Is a Failure to Communicate" The general communications from authorities, from the CDC to the FDA and the USDA, have until now been lackluster at best. At the start of what could easily be an entirely new pandemic, this is disturbing. The first and most obvious place to start would be getting farmers on board with how severe this could be and how much they are at risk. We need their help. Instead, it appears that the USDA and the FDA have been delegated to deal rather casually with the farms in question. Thus, no required testing, surveillance, or PPE are in effect as policies. The early days of the cattle outbreak have been, in fact, defined by the dumping of badly infected milk into what are called "milk lagoons": open, outdoor ponds of milk. While pasteurized milk appears to be potentially safe (with the virus present inactivated in the process), raw milk is not. This may explain the deaths of many cats near dairies (50% mortality rate) and the extremely bad news that H5N1 has now been found in mice, drastically increasing the chances of human exposure and, thus, a global pandemic. The USDA is apparently now trying a program to pay farmers to treat infected milk. This is smart, but late, and the jury is still out on whether it will work. Meanwhile, there are some alarming matters going relatively undiscussed. There is not a readily available antigen detection test for H5N1, so Flu A antigen detection tests are the first line of defense, followed by individual diagnoses. These Flu A tests are specifically noted, however, to be potentially too low in sensitivity to detect H5N1 - which would be a serious issue. This must obviously be remedied as soon as possible, but for now detecting Flu A in the population should be a warning sign - particularly since the Northern Hemisphere is no longer in flu season. Luckily, the CDC has a new online tool for tracking influenza in the sewershed. Oddly enough, its website notes that this and other tools are being monitored and that "[t]aken together, these systems currently show no indicators of unusual flu activity in people, including avian influenza A(H5N1) (bird flu)." The problem with this is that it isn't quite true, or at least it's a bit of wordplay. The Flu A wastewater surveillance doesn't show signs of anything in people. It shows signs of things in the sewer. But that doesn't mean it should be ignored. In fact, over the past month, we at SNS have tracked the Flu A wastewater maps. The locations with cattle outbreaks are often featured.

Map of areas with Influenza A wastewater levels above average and higher for the week of May 18.

Map of areas with Influenza A wastewater levels above average and higher for the week of May 25. Maps courtesy CDC While it appears to have subsided, April/May saw a massive surge in Influenza A in the heart of the Bay Area. Although this could be from any of a number of causes, a huge uptick in Flu A during a potential Flu A pandemic but outside of the normal flu season should be openly discussed, investigated, and generally acknowledged. Meanwhile, many of the sites around the country do not meet criteria for reporting. This is still flying half-blind. The public will need far better descriptions of what is being done on disease surveillance for reassurance, as well. The information ecosystem abhors a vacuum. As public communication fails, mis- or disinformation will replace it. Transparency and open communication are not just ethical; they also prevent worse outcomes. There is already rampant speculation across social media about things like the surges in Flu A in wastewater. What's worse, there are already online actors pushing the idea that people should drink infected, unpasteurized milk on purpose for inoculation. It's already clear that this virus is going to be hard to contain; good communication and real transparency are going to be a prerequisite to even trying.

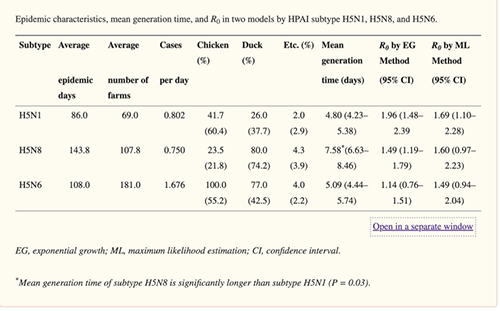

In some cases the dead were left in their homes for days. Private undertaking houses were overwhelmed, and some were taking advantage of the situation by hiking prices as much as 600 percent. Complaints were made that cemetery officials were charging fifteen-dollar burial fees and then making the bereaved dig the graves for their dead themselves. - Alfred Crosby, America's Forgotten Pandemic, The Influenza of 1918 The potential severity of an H5N1 pandemic makes awareness and preparedness critical. If a human-to-human transmission event occurs, we can expect things will be dire in the absence of serious intervention. Traditionally, the case fatality rate (CFR) of H5N1 hovers somewhere between 50% and 60%. That means one-half of those documented as having contracted it do not survive. This number is almost guaranteed to be an overestimate, since the extreme cases get documented, and those that are asymptomatic may not. But even so, as a species, our previous encounters with avian flu have not been good. One study has attempted to understand what the real fatality rate might be. Its conclusion reads: We suggest that, based on surveillance and seroprevalence studies conducted in several countries, the real H5N1 CF rate should be closer to 14-33%. Conclusions: Clearly, if such a CF rate were to be sustained in a pandemic, H5N1 would present a truly dreadful scenario. A concerted and dedicated effort by the international community to avert a pandemic through combating avian influenza in animals and humans in affected countries needs to be a global priority. If the fatality rate were between 14% and 33%, the next factor to consider would be the "attack rate." In other words, to understand whether a pathogen is an existential threat, we need to know both how deadly it is and how easily it spreads. This is measured by the reproductive number, R0 (pronounced "r naught"), representing the number of other people who will be infected by each infected individual. There are some other factors, such as the serial interval including incubation and contagious periods (how long it takes to become infective, how long you're contagious and spreading a pathogen). We cannot know the R0 for a pathogen that doesn't yet exist - a "new" mutated version will have to occur to begin spreading in people in the first place. A pair of researchers in Seoul, Korea, tried to estimate for a potential H5N1 R0 for animals based on avian outbreaks. They came up with the below chart, showing an estimated R0 for H5N1 in birds at 1.96. This is sustained transmission (everything above 1 is, as it means that more than 1 other individual is being infected, and thus exponential growth occurs) - albeit far less contagious than COVID, which now has an R0 somewhere between 5 and 9. But we are not chickens, and we do not know what a human-to-human H5N1 variant might look like yet. Suffice it to say that a pandemic of this pathogen would likely look a lot more like 1918 than 2020. If we think back on how much disruption occurred in the early days of a virus that killed 1% of those infected, imagine one that, while it may move slower, kills 10 times as many people. A pandemic of that proportion would challenge our ability to maintain continuity of services.

In our current political situation, it may seem as if few people would ever agree to go back to any form of PPE or staying at home, a death rate of that magnitude would likely change public opinion on the importance of mitigation very fast. Nothing can change our world in an instant quite like a deadly pathogen.

Plan for what is difficult while it is easy, do what is great while it is small. - Sun Tzu By now, it should be clear that we are already in the middle of the next pandemic. So far, it's been one of birds, seals, foxes, alpacas, goats, mice, bears . . . the list goes on and on. We as a species would be naive to believe that, through some sort of sheer hubris, we are not next. In a recent preprint of a study of the Argentinian elephant seal outbreak, performed by the University of California Davis's School of Veterinary Medicine and Argentina's National Institute of Agriculture and Technology, UC Davis notes that researches showed: [. . .] clear mammal-to-mammal transmission of the virus. It states the outbreak is the first known, multinational transmission of the virus in mammals ever observed globally, with the same virus appearing in several pinniped species across different countries over a short period of time. This is an extremely dangerous situation that should be taken as seriously as any threat to public health in human history. Right now, we have a brief moment to assess and prepare. Many gears in the US government are already turning. The USDA, the FDA, and the CDC all appear to be working hard to remedy some of the shortfalls to date. But this all needs to happen better, and faster. So, what do we actually need to be doing? Let's take a look at the two categories that matter most: policy and personal. Policy

"Regarding epidemiologic and scientific investigations, federal officials last week announced - as part of new support for farms and the outbreak response - a $75 financial incentive for farm workers at affected dairy farms to be tested. [Nirav Shah, the CDC's principal deputy director] said so far the CDC hasn't identified any workers who are willing to participate. He added that the CDC is eager to conduct testing to answer key questions, such as which farm jobs pose the highest risk to workers. There are no plans to add a testing requirement, Shah said. "We would like to do this in voluntary cooperation with farms and farm workers." That isn't going to work. Many workers are undocumented and may avoid any interactions with authorities unless required. They may need to be given immunity from prosecution or deportation as a safeguard. Disease surveillance must be dramatically increased on US farms, and testing required. Otherwise, infected workers will simply spread disease. Control of the situation is rendered impossible unless testing is mandatory. An individual should not be permitted to decide whether they wish to prevent a pandemic for the other 8 billion people living on this planet. Lives are at stake.

Personal

Master that skill.

A Hard But Necessary Conversation It seems appropriate, given the gravity of this piece, to add a few notes here. As you know, we often cover difficult topics in this publication. Given the trauma and exhaustion of the past four years, this is obviously a hot-button subject. It's a lot to process, and a lot to have on our plates. It's important that it's clear, then, that we publish this not to cause panic, fear, or uncertainty, but the opposite. Before the COVID pandemic, we warned you it was coming. In this case, we are warning that one is now likely imminent, though that could change (we'll let you know if it does). The point of doing so is not to add stress to your lives, but to keep you informed, healthy, happy, and successful, as we have always sought to do. I hope this information and analysis have been useful and informative, even if it is stressful. I hope it will serve you in your lives, at work and at home, to understand the situation as it is. These days, a lot of effort in media and public communications is given to telling people the situation as we might wish it to be. We don't do that.

Your comments are always welcome.

Sincerely, Evan Anderson DISCLAIMER: NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE Information and material presented in the SNS Global Report should not be construed as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained in this publication constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer by Strategic News Service or any third-party service provider to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments. This publication is not intended to be a solicitation, offering, or recommendation of any security, commodity, derivative, investment management service, or advisory service and is not commodity trading advice. Strategic News Service does not represent that the securities, products, or services discussed in this publication are suitable or appropriate for any or all investors. We encourage you to forward your favorite issues of SNS to a friend(s) or colleague(s) 1 time per recipient, provided that you cc info@strategicnewsservice.com and that sharing does not result in the publication of the SNS Global Report or its contents in any form except as provided in the SNS Terms of Service (linked below). To arrange for a speech or consultation by Mark Anderson on subjects in technology and economics, or to schedule a strategic review of your company, email mark@stratnews.com. For inquiries about Partnership or Sponsorship Opportunities and/or SNS Events, please contact Berit Anderson, SNS COO, at berit@stratnews.com.

Subject: Re: "SNS: A NEW ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE" Mark, I last read that those Chinese come for freedom. They don't. They come to buy a house and to avoid arrest for getting the money through corruption. Today's (San Jose) Mercury News reports that nearly half of California's homeless are over 50, and the percentage is going up. Homeless retirement, the American Dream brought to you by the woke one-party state. What are the odds that these problems will get worse?

Scott Foster Journalist, Asia Times

Subject: Re: Ep. 6 w/ David Brin: Is NASA's Moon Race a Distraction? Berit, Terrific, Berit. Already touted online! Was nice having Mark [Anderson] and Denyse [Hudson] here at our home, yesterday. Thrive. And persevere!

Author and Physicist

David, Thank you so much! This was a really fun conversation - as I'm sure yours was last night. Hope to do it again soon sometime on another topic.

* On June 19, Mark will be hosting the annual Pattern Investor event at the Woodmark Hotel in Redmond, WA; for your complimentary reservation and to invite others, contact Laura Oye at laura@patterncomputer.com. * On October 20-23, he will be speaking on a variety of subjects, and hoping to see many of our members in person, at the FiRe 2024 conference at the Terranea resort in Palos Verdes, California.

Copyright 2024 Strategic News Service LLC "Strategic News Service," "SNS," "Future in Review," "FiRe," "INVNT/IP," and "SNS Project Inkwell" are all registered service marks of Strategic News Service LLC. ISSN 1093-8494 |